Bates Research | 10-02-25

Is Your Institution at Risk for Ponzi Scheme Liability?

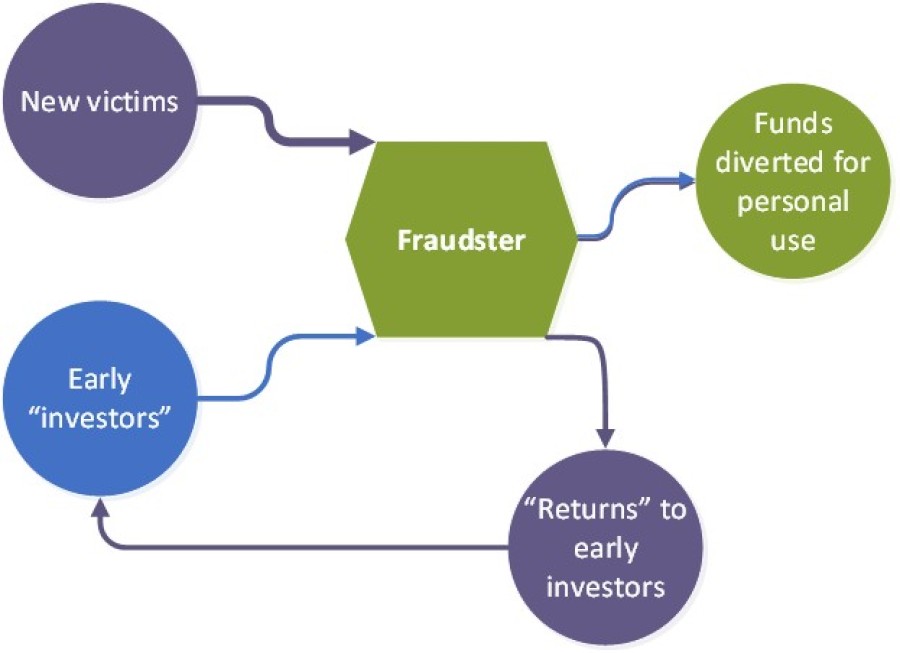

Ponzi schemes differ from other financial schemes in that they offer a purported return on investment, with the “return” actually being funded by new investor contributions. Some Ponzi schemes never even invest funds in an actual investment vehicle. In order for the scheme to appear to generate returns for early investors (and therefore attract more investors to the scheme), Ponzi schemes in the modern era almost always involve money flowing through financial institutions. Many fraudsters use multiple institutions and mix fraudulent transactions with legitimate banking activity, making it difficult for any one institution to recognize its role in the scheme.

How Ponzi Schemes Appear in Practice

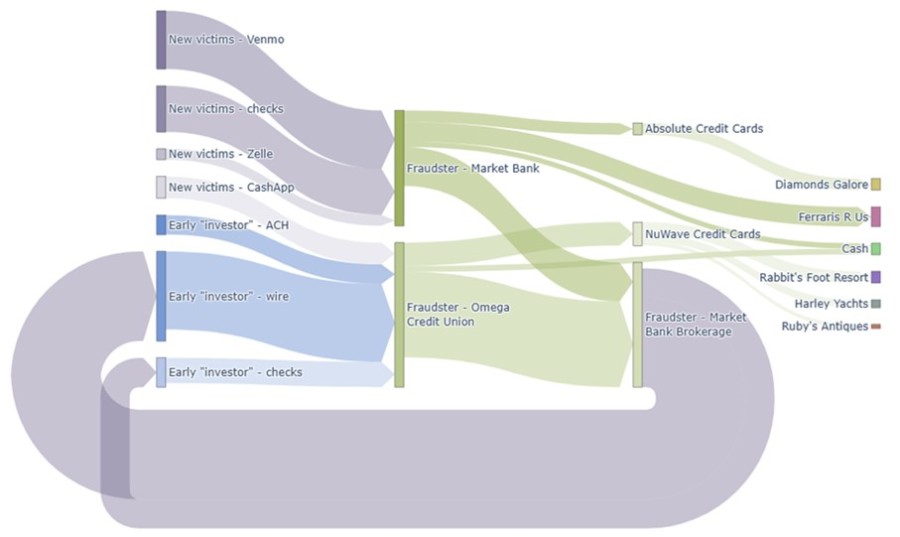

Fraud investigators and analysts help unravel Ponzi scheme transactions by painting a complete picture using all relevant pieces of information, which shows how a blend of old-school and new-wave transaction methods can obfuscate Ponzi transaction flows. For example, a summary view of a Ponzi-type scheme may appear straightforward:

However, the actual machinations of the scheme are likely much more complicated, creating a complex web that can only be untangled through detailed analysis of a variety of data (e.g., transaction records, check images, wire details).

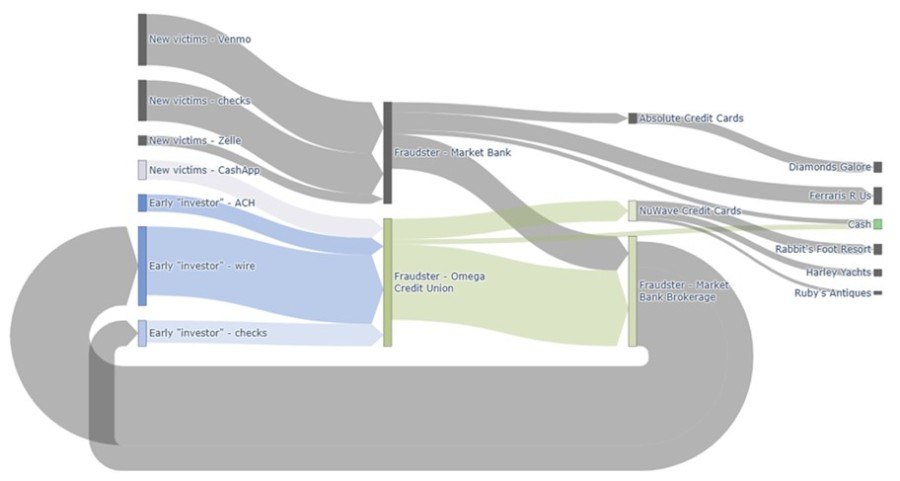

Because each institution sees only part of the picture, fraudsters often succeed in hiding their activity until the scheme collapses. In the above example, Omega Credit Union only has insight to see that their customer received funds via CashApp, ACH, wire, and traditional check deposit, and then paid a credit card bill, withdrew some cash, and transferred funds to an external brokerage.

It could be very difficult for Omega to understand they are part of a scheme at all, but there are some common warning signs a financial institution can design programs to detect.

Indicators of Ponzi Schemes to Watch For

- Large volumes of unusual service requests, address or account changes, and frequent addition or removal of authorized signers.

- Patterns of rapid movement of funds from one account to another with no apparent business purpose, including transfers from business to personal accounts, including same-day transfers to avoid overdrafts.

- Requests for employees to provide references to third parties or to assure others that funds are “safe” with the customer.

- Large numbers of wire transfers or ACH transfers initiated by phone or online.

Additional red flags include chronic overdrafts, misdirected or withheld account statements, and inquiries or complaints from investors or regulators.

Related Insight: How To File a Defensible SAR

Why Ponzi Cases Can Be Challenging

Litigation often turns on whether insiders at the institution had “reason to know” of fraud based on the presence of indicators such as those above. Plaintiffs may argue that institutions either should have investigated further or knew so much through due diligence and AML monitoring that they must have been aware of the fraud. Automated AML systems typically generate many alerts on high-activity accounts, creating further litigation risk: plaintiffs may portray ignored alerts as negligence, or acknowledged alerts as evidence of complicity.

At trial, courts often focus on whether insiders had actual knowledge of issues such as:

- Signs the fraudster was insolvent.

- Promises made to investors.

- Diversion of investor funds for personal use.

Typical Defenses

Financial institutions often assert defenses such as:

- The institution had no actual knowledge of the scheme. (State laws differ on whether plaintiff must prove actual knowledge or if constructive knowledge is sufficient.)

- Aiding and abetting liability requires both knowledge and substantial assistance.

- Court-appointed receivers may lack standing to sue.

- Some states bar claims on grounds that multiple parties are equally at fault (in pari delicto).

- Applicable statutes of limitation.

Defending in Hindsight

Ponzi-related liability cases are difficult to defend and nearly impossible to prevent entirely. Institutions must prepare for how their treatment of customers will be judged in hindsight. At trial, the strongest position is often to demonstrate that:

- Due diligence at account opening established a clear understanding of the customer’s business.

- Documentation accurately reflected the customer relationship.

- Employees were trained to recognize and escalate suspicious activity.

- AML alerts were reviewed, managed, and documented in a way consistent with the risks presented.

How Bates Group Helps

Bates Group has a long history of efficiently analyzing large volumes of financial records to provide a complete picture of potential exposure. We can provide easy-to-understand graphics of the data analyzed to help your legal team understand potential exposure and develop a comprehensive strategy. Bates Group consultants can also assist financial institutions to take a proactive approach by designing due diligence procedures and controls, employee training, and AML surveillance management, ensuring that staff are prepared to recognize and report unusual activity. Our team has supported institutions in defending Ponzi-related claims and has provided expert testimony at trial.

Contact us Today to Schedule a Consultation

Author Links

Frederick Egler

Testifying Expert